The Internet

explained from first principles

Cite this article

You can cite this article in various citation styles as follows:

| MLA: | Etter, Kaspar. “The Internet explained from first principles.” Explained from First Principles, 5 Aug. 2020, https://explained-from-first-principles.com/internet/. Accessed . |

|---|---|

| CMOS: | Etter, Kaspar. “The Internet explained from first principles.” Explained from First Principles, August 5, 2020. Accessed . https://explained-from-first-principles.com/internet/. |

| APA: | Etter, K. (2020, August 5). The Internet explained from first principles. Explained from First Principles. Retrieved , from https://explained-from-first-principles.com/internet/ |

| IEEE: | K. Etter, “The Internet explained from first principles,” Explained from First Principles, Aug. 5, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://explained-from-first-principles.com/internet/. [Accessed: ]. |

| BibTeX: |

@misc{etter_2020_the_internet,

title = {The Internet explained from first principles},

url = {https://explained-from-first-principles.com/internet/},

journal = {Explained from First Principles},

author = {Etter, Kaspar},

date = {2020-08-05},

year = {2020},

month = {Aug},

day = {5},

edition = {2021-10-21},

urldate = {}

}

|

If you are worried about the persistence of this website, you can link to the latest snapshot of the Internet Archive instead.

If you are visiting this website for the first time, then please first read the front page, where I explain the intention of this blog and how to best make use of it. As far as your privacy is concerned, all data entered on this page is stored locally in your browser unless noted otherwise. While I researched the content on this page thoroughly, you take or omit actions based on it at your own risk. In no event shall I as the author be liable for any damages arising from information or advice on this website or on referenced websites.

Preface

I wrote this article to introduce the Internet to a non-technical audience. In order to get everyone on board, I first explain basic concepts, such as communication protocols, network topologies, and signal routing. The section about Internet layers becomes increasingly technical and peaks with a deep dive into DNSSEC. If the beginning is too elementary for you, then just skip ahead to more interesting sections.

Due to the nature of the topic, this article contains a lot of acronyms. Many of them are three-letter acronyms (TLA), but some are longer, which makes them extended three-letter acronyms (ETLA). While I introduce all acronyms before using them, you can simply hover over a TLA or an ETLA with your mouse if you forgot what they stand for. If you are reading this on a touch device, you have to touch the acronym instead.

Let’s get right into it: What is a protocol?

Communication protocol

Communication diagram

A communication protocol specifies how two parties can exchange information for a specific purpose. In particular, it determines which messages are to be transmitted in what order. If the two parties are computers, a formal, well-defined protocol is easiest to implement. In order to illustrate what is going on, however, let’s first look at an informal protocol, also known as etiquette, which we’re all too familiar with:

This is a sequence diagram. It highlights the temporal dimension of a protocol in which messages are exchanged sequentially.

Communication parties

It also illustrates that communication is commonly initiated by one party, whereby the recipient responds to the requests of the initiator. Please note that this is only the case for one-to-one protocols, in which each message is intended for a single recipient.

Broadcasting and information security

There are also one-to-many protocols for broadcasting. These are typically one-way protocols, in which the recipients do not acknowledge the receipt of the transferred data. Examples for such protocols are analog radio or churches ringing their bells to indicate the time of day. Both in the case of a single recipient and in the case of a broad target audience, anyone with access to the physical medium and the right sensors receives the signal. The difference is simply that, in the former case, entities ignore the messages which are not addressed to them. If the messages are not encrypted, others can still read them, though. And if the messages are not authenticated, a malicious party might be able to alter them in transit. Even when messages are encrypted and authenticated, their exchange can still be interrupted, by not relaying some messages or by jamming the signal. The properties Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability form the so-called CIA triad of information security.

Communication channel

The above greeting protocol is used among humans to establish a communication channel for a longer exchange. In technical jargon, such an exchange in preparation for the actual communication is called a handshake. The greeting protocol checks the recipient’s availability and willingness to engage in a conversation. When talking to someone you have never spoken before, it also ensures that the recipient understands your language. I’ve chosen these two examples for their figurative value. Why we actually greet each other is mainly for different reasons: To show our good intentions by making our presence known to each other, to signal sympathy and courtesy by asking the superficial question, and to indicate our relative social status to each other and to bystanders. Another benefit of asking such a question is that, even though it’s very shallow, it makes the responder more likely to do you a favor due to the psychological effect of commitment and consistency.

Handling of anomalies

Protocol deviation

Since your communication partner can be erratic, a protocol needs to be able to handle deviations:

Data corruption

Sometimes, data becomes unintelligible in transit, for example due to a lot of background noise:

In order to detect transmission errors, computers typically append a checksum to each message, which the recipient then verifies. The need to retransmit messages can be reduced by adding redundancy to messages so that the recipient can detect and correct small errors on their own. A simple and very inefficient way of doing this is to repeat the content within each message several times.

Connection loss

It can also happen that a party loses their connection permanently, for example by moving too far away for the signal to reach the recipient. Since a conversation requires some attention from the communication partner, abandoning a conversation unilaterally without notifying the other party can be misused to block them from talking to someone else for some time. In order to avoid binding resources for a prolonged period of time and thereby potentially falling victim to a so-called denial-of-service attack, computers drop connections after a configurable duration of inactivity:

Network latency

Other times, your communication partner is simply slow, which needs to be accommodated to some degree:

Out-of-order delivery

The following rarely occurs between humans but as soon as messages are passed over various hops, such as forwarding notes among pupils in a classroom, they can arrive out of order:

The solution for this is to enumerate all messages, to reorder them on arrival, and to ask the other party to retransmit any missing messages, as we saw above.

Lack of interoperability

Besides defining the syntax (the format), the semantics (the meaning), and the order of the messages, a protocol should also specify how to handle anomalies like the above. Ambiguity in a standard and willful deviation therefrom result in incompatibilities between different implementations. In combination with a lack of established standards in many areas, which often leads to uncoordinated efforts by various parties, incompatibilities are quite common in computer systems, unfortunately. This causes a lot of frustration for users and programmers, who have to find workarounds for the encountered limitations, but this cannot be avoided in a free market of ideas and products.

Network topologies

Communication network

In practice, there are almost always more than two parties who want to communicate with each other. Together with the connections between them, they form a communication network. For the scope of this article, we’re only interested in symmetric networks, where everyone who can receive can also send. This is not the case for analog radio and television networks, where signals are broadcasted unidirectionally from the sender to the receivers. In the case of our symmetric networks, two entities are part of the same network if they can communicate with each other. If they cannot reach each other, they belong to separate networks.

Nodes and links

Nodes are the entities that communicate with each other over communication links. We can visualize this as follows:

The terminology is borrowed from graph theory, where nodes are also called vertices and links are also called edges. The technical term for the structure of a network is topology. Different arrangements of nodes and links lead to different characteristics of the resulting network.

Fully connected network

A network is said to be fully connected if every node has a direct link to every other node:

In graph theory, such a layout is known as a complete graph. Fully connected networks scale badly as the number of links grows quadratically with the number of nodes. You might have encountered the formula for the number of links before: n × (n – 1) / 2, with n being the number of nodes in the network. As a consequence, this topology is impractical for larger networks.

Star network

The number of links can be reduced considerably by introducing a central node, which forwards the communication between the other nodes. In such a star-shaped network, the number of links scales linearly with the number of nodes. In other words, if you double the number of nodes, you also double the number of links. In a fully connected network, you would have quadrupled the number of links. For now, we call the newly introduced node a router. As we will see later on, such a relaying node is called differently depending on how it operates. Nodes that do not forward the communication of others form the communication endpoints of the network.

While a star network scales optimally, it is by definition totally centralized. If the nodes belong to more than one organization, this topology is not desirable as the central party exerts complete control over the network. Depending on its market power, such a party can increase the price for its service and censor any communication it doesn’t like. Additionally, the central node becomes a single point of failure: If it fails for whatever reason, then the whole network stops working. Since this lowers the availability of the network, the star topology should not just be avoided for political but also for technical reasons.

Mesh network

We can avoid these drawbacks by increasing the number of nodes which forward the communication between the endpoints:

In this graph, any of the three routers can go down, and communication is still possible between the nodes that are connected not only to the unavailable router. There are also five links that can break one at a time while leaving all nodes indirectly connected with each other. Such a partially connected network allows for a flexible tradeoff between redundancy and scalability. It is therefore usually the preferred network topology. Furthermore, the node marked with an asterisk is connected to two routers in order to increase its availability. Because of higher costs, this is usually only done for critical systems, which provide crucial services.

Signal routing

Network addresses

Unlike in a fully connected network, where each node can simply pick the right link to reach the desired node, a network with relay nodes requires that nodes can address each other. Even if a router relays each signal on all of its links to other nodes, which would make it a hub instead of a router, the nodes still need a way to figure out whether they were the intended recipient of a message. This problem can be solved by assigning a unique identifier to each node in the network and by extending each transmitted message with the identifier of the intended recipient. Such an identifier is called a network address. Routers can learn on which link to forward the communication for which node. This works best when the addresses aren’t assigned randomly but rather reflect the – due to its physical nature often geographical – structure of the network:

We’re all familiar with hierarchical addresses such as postal codes, which are known as ZIP Codes in the United States, and telephone numbers with their country calling codes. Strictly speaking, the address denotes the network link of a node and not the node itself. This can be seen in the node on the right, which is known as B2 to router B and as C1 to router C. In other words, if a node belongs to several so-called subnetworks, such as B and C in this example, it also has several addresses.

Routing tables

The process of selecting a path between two nodes across a network is called routing. Routers are the nodes which perform the routing. They maintain a routing table so they know on which link to forward the communication for each node:

| Destination | Link | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1 | 4 |

| A2 | 2 | 2 |

| B? | 3 | 5 |

| B? | 4 | 8 |

| C? | 3 | 9 |

| C? | 4 | 6 |

It contains all the destinations to be reached.

The links are numbered according to the above graphic.

This table tells router A, for example, to forward all communications for node A2 on link 2. It doesn’t matter on which link router A receives such communications. The router also keeps track of how costly each route is. The cost can either be in terms of network delay or the economic cost of the transmission, based on what providers charge each other. In this example, router A forwards all communications for nodes starting with C on link 4 because the associated cost is lower than the cost for link 3 via router B.

Forwarding tables

To be precise, the routing table contains all routes, even the ones which aren’t optimal regarding the associated costs. Based on this information, a router constructs the actual forwarding table, which only contains the optimal route for each destination without its cost. This makes the table smaller and the lookup during routing faster, which is important for low latency.

| Destination | Link |

|---|---|

| A1 | 1 |

| A2 | 2 |

| B? | 3 |

| C? | 4 |

Routing protocols

Routers and the physical links between them can fail at any time, for example because a network cable is demolished by nearby construction work. On the other hand, new nodes and connections are added to communication networks all the time. Therefore, the routing tables of routers need to be updated continuously. Instead of updating them manually, routers communicate changes with each other using a routing protocol. For example, as soon as router A detects that it’s no longer getting a response from router C, it updates its routing table to route all communication to C via B:

| Destination | Link | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1 | 4 |

| A2 | 2 | 2 |

| B? | 3 | 5 |

| C? | 3 | 9 |

Signal relaying

A signal can be relayed through a network either with circuit switching or with packet switching.

Circuit switching

In a circuit-switched network, a dedicated communications channel is established between the two parties for the duration of the communication session:

The best-known example of a circuit-switched network is the early telephone network. In order to make a call, a switchboard operator needed to connect the wires of the two telephones in order to create a closed circuit. This has the advantage that the delay of the signal remains constant throughout the call and that the communication is guaranteed to arrive in the same order as it was sent. On the other hand, establishing a dedicated circuit for each communication session can be inefficient as others cannot utilize the claimed capacity even when it’s temporarily unused, for example when no one is speaking.

Packet switching

In a packet-switched network, the data to transfer is split into chunks. These chunks are called packets and consist of a header and a payload. The header contains information for the delivery of the packet, such as the network address of the sender and the recipient. Each router has a queue for incoming packets and then forwards each packet according to its routing table or, more precisely, its forwarding table. Apart from these tables, packet-switching routers do not keep any state. In particular, no channels are opened or closed on the routing level.

Since each packet is routed individually, they can take different routes from the sender to the recipient and arrive out of order due to varying delays.

Since no router has a complete view of the whole network, it could happen that packets get stuck in an infinite loop:

In order to avoid wasting network resources, the header of a packet also contains a counter, which is decreased by one every time it passes a router. If this counter reaches zero before the packet arrives at its destination, then the router discards the packet rather than forwarding it. Such a counter limits the lifespan of a packet by limiting the number of hops it can take and is thus known as its time-to-live (TTL) value. There are also other reasons why a packet can get lost in the network. The queue of a router might simply be full, which means that additional packets can no longer be stored and must therefore be dropped. Because packets are similar to cars on the road network, some terms are borrowed from the transportation industry. While the capacity of a packet-switched network can be utilized better than the capacity of a circuit-switched network, too much traffic on the network leads to congestion.

Source and destination addresses

Because routers keep no records regarding the route that a packet took, the response from the recipient has to include the address of the original sender. In other words, the sender has to disclose its own address to the recipient in order to be able to get a response. This is why packets always include two addresses: the one of the source and the one of the destination.

Internet layers

The Internet is a global network of computer networks. Its name simply means “between networks”. It is a packet-switched mesh network with only best-effort delivery. This means that the Internet provides no guarantees about whether and in what time a packet is delivered. Internet service providers (ISP) provide access to the Internet for businesses and private individuals. They maintain proprietary computer networks for their customers and are themselves interconnected through international backbones. The big achievement of the Internet is making individual networks interoperable through the Internet Protocol (IP).

The Internet operates in layers. Each layer provides certain functionalities, which can be fulfilled by different protocols. Such a modularization makes it possible to replace the protocol on one layer without affecting the protocols on the other layers. Because the layers above build on the layers below, they are always listed in the following order but then discussed in the opposite order:

| Name | Purpose | Endpoints | Identifier | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application layer | Application logic | Application-specific resource | Application-specific | HTTP |

| Security layer | Encryption and authentication | One or both of the parties | X.509 subject name | TLS |

| Transport layer | Typically reliable data transfer | Operating system processes | Port number | TCP |

| Network layer | Packet routing across the Internet | Internet-connected machines | IP address | IP |

| Link layer | Handling of the physical medium | Network interface controllers | MAC address | Wi-Fi |

We will discuss each layer separately in the following subsections. For now, you can treat the above table as an overview and summary. Before we dive into the lowest layer, we first need to understand what “building on the layer below” means. Digital data can be copied perfectly from one memory location to another. The implementation of a specific protocol receives a chunk of data, known as the payload, from the layer above and wraps it with the information required to fulfill its purpose in the so-called header. The payload and the header then become the payload for the layer below, where another protocol specifies a new header to be added. Each of these wrappings is undone by the respective protocol on the recipient side. This can be visualized as follows:

While this graphic is useful to wrap your head around these concepts, it can be misleading in two ways. Firstly, the payload can be transformed by a specific protocol as long as the original payload can be reconstructed by the recipient. Examples for this are encryption and redundant encoding for automatic error detection and correction. Secondly, a protocol can split a payload into smaller chunks and transfer them separately. It can even ask the sender to retransmit a certain chunk. As long as all the chunks are recombined on the recipient side, the protocol above can be ignorant about such a process. As we’ve seen in the sections above, a lot of things can go wrong in computer networks. In the following subsections, we’ll have a closer look on how protocols compensate for the deficiencies of the underlying network. Before we do so, we should talk about standardization first.

Request for Comments (RFC)

When several parties communicate with each other, it’s important that they agree on a common standard. Standards need to be proposed, discussed, published, and updated to changing circumstances. I’m not aware of any laws that impose specific networking standards outside of governmental agencies. The Internet is an open architecture, and technology-wise, you’re free to do pretty much anything you want. This doesn’t mean, though, that others will play along. If different companies shall adopt the same standards to improve interoperability, it’s very useful to have independent working groups, in which proposed standards are discussed and approved. For Internet-related standards, such an open platform is provided by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) with organizational and financial support from the Internet Society (ISOC). Workshop participants and managers are typically employed by large tech companies, which want to shape future standards.

The IETF publishes its official documents as Requests for Comments (RFCs). This name was originally chosen to avoid a commanding appearance and to encourage discussions. In the meantime, early versions of potential RFCs are published as Internet Drafts, and RFCs are only approved after several rounds of peer review. RFCs are numbered sequentially, and once published, they are no longer modified. If a document needs to be revised, a new RFC with a new number is published. An RFC can supersede earlier RFCs, which are then obsoleted by the new RFC. Sometimes, RFCs are written after the documented technique has already gained popularity. Even though the most important Internet protocols are specified in RFCs, their conception and style is much more pragmatic than similar documents of other standards organizations. The first RFC was published in 1969. Since then, almost 9’000 RFCs have been published. Not all RFCs define new standards, some are just informational, some describe an experimental proposal, and others simply document the best current practice.

Link layer

Protocols on the link layer take care of delivering a packet over a direct link between two nodes. Examples of such protocols are Ethernet and Wi-Fi. Link layer protocols are designed to handle the intricacies of the underlying physical medium and signal. This can be an electric signal over a copper wire, light over an optical fiber or an electromagnetic wave through space. The node on the other end of the link, typically a router, removes the header of the link layer, determines on the network layer on which link to forward the packet, and then wraps the packet according to the protocol spoken on that link. Link layer protocols typically detect bit errors caused by noise, interference, distortion, and faulty synchronization. If several devices want to send a packet over the same medium at the same time, the signals collide, and the packets must be retransmitted after a randomly chosen backoff period.

Number encoding

Numbers are used to quantify the amount of something, and just like you can have only more, less, or an equal amount of a quantity, a number must be either larger than, less than, or equal to any other number (as long as we talk about real numbers only). Numbers can therefore be thought of as points on a line. While numbers as concepts exist independently of the human mind (if we assume mathematical realism), we need a way to express numbers when thinking, speaking, and writing about them. We do so by assigning labels and symbols to them according to a numeral system. For practical reasons, we have to rely on a finite set of symbols to represent an infinite set of numbers. To make this possible, we have to assign meaning to the order, position, and/or repetition of symbols. With the exception of tally marks, only the positional notation is relevant nowadays.

In positional notation, you have an ordered list of symbols, representing the values from zero to the length of the list minus one. In the commonly used decimal numeral system, there are ten symbols, also called digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. (The name “digit” comes from the Latin “digitus”, which means finger.) As soon as you have used up all the symbols, you create a new position, usually to the left. The represented number is the index of the symbol in this new position multiplied by the length of the list plus the index of the symbol in the initial position. Each time you went through all the symbols in the right position, you increment the left position by one. Two positions of ten possible symbols allow you to represent 102 = 100 numbers. Since zero is one of them, you can encode all numbers from 0 to 99 with these two positions. The symbol in the third position counts how many times you went through the 100 numbers. It is thus multiplied by 102 before being added up. The symbol in the fourth position is multiplied by 103, and so on. All of this should be obvious to you. However, you might not be used to using less than or more than ten symbols.

The binary numeral system uses, as the name suggests, only two symbols, typically denoted as 0 and 1. You count according to the rules described above: After 0 and 1 comes 10 and 11, which in turn are followed by 100, 101, 110, and 111. Each position is called a bit, which is short for “binary digit”. Just as with decimal numbers, the most significant bit is to the left, the least significant bit to the right. Since there are only two elements in the list of symbols, the base for exponentiation is 2 instead of 10. If we count the positions from the right to the left starting at zero, each bit is multiplied by two raised to the power of its position. 4 bits allow you to represent 24 = 16 numbers, and 8 bits allow you to represent 28 = 256 numbers.

Virtually all modern computers use the binary numeral system because each bit can be encoded as the presence or absence of a physical phenomenon, such as voltage or electric current. This makes operations on binary numbers quite easy to implement in electronic circuits with logic gates. Since 0 and 1 don’t encode a lot of information, the smallest unit of computer memory that can be addressed to load or store information is typically a byte, which is a collection of eight bits. Instead of the eight bits, a byte is often represented for humans as a number between 0 and 255 or as two hexadecimal symbols. The latter assigns one symbol to four bits. Since 4 bits encode 16 numbers, the 10 digits are supplemented by 6 letters, resulting in the symbols 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, and F. The F in hexadecimal notation stands for 15 in decimal notation and 1111 in binary notation.

What I just wrote only applies to natural numbers, also called unsigned integers. Negative integers are included by using the leftmost bit for the sign: Positive numbers start with a zero, negative numbers with a one. The actual encoding is a bit more complicated because it is chosen such that the implementation of addition, subtraction, and multiplication is the same for signed and unsigned integers. Floating point numbers are even more complicated and beyond the scope of this article.

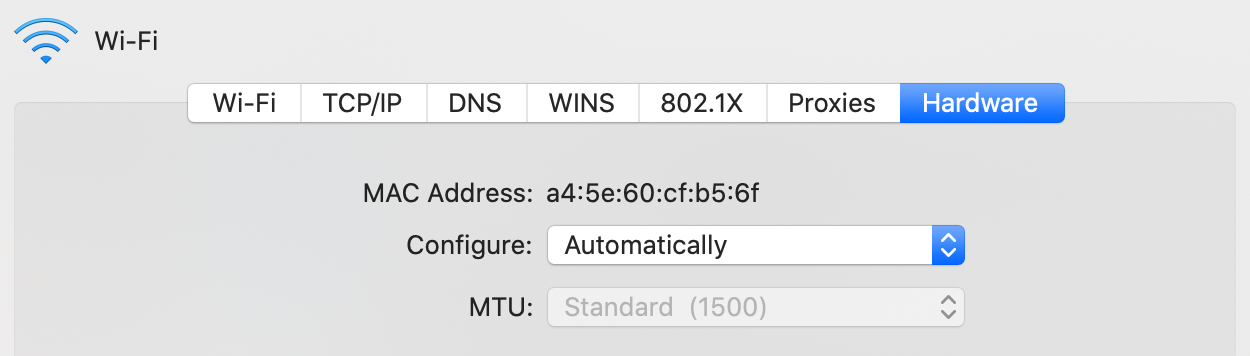

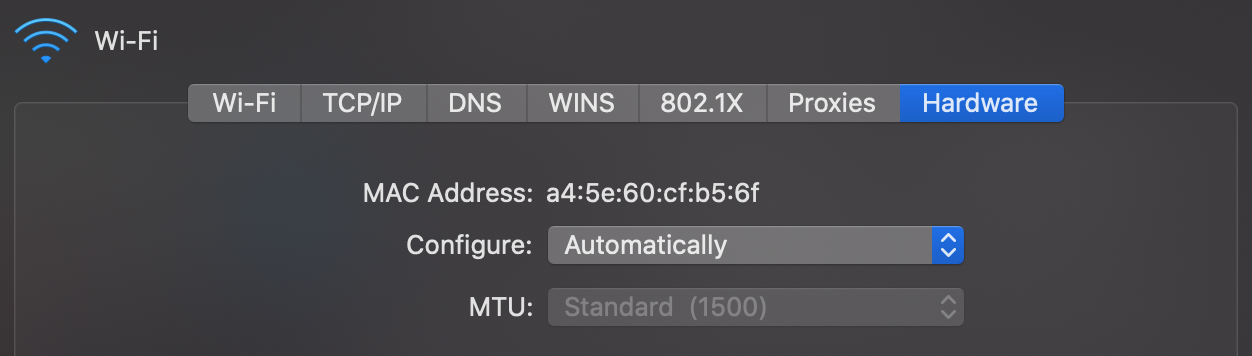

Media access control (MAC) address

The media access control (MAC) address is commonly used as the network address on the link layer. It is a 48-bit number, which is typically displayed as six pairs of hexadecimal digits. (One hexadecimal digit represents 4 bits, so twelve hexadecimal digits represent 48 bits.) MAC addresses are used in Ethernet, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth to address other devices in the same network. Historically, they were assigned by the manufacturer of the networking device and then remained the same throughout the lifetime of the device. Since this allows your device to be tracked, operating systems started randomizing MAC addresses when scanning for Wi-Fi networks after the revelations by Edward Snowden. According to Wikipedia, MAC address randomization was added in iOS 8, Android 6.0, Windows 10, and Linux kernel 3.18.

Hubs, switches, and routers

When I talked about network topologies, I simply called relaying nodes “routers”, but there are actually three types of them:

- A hub simply relays all incoming packets to all other links.

- A switch remembers which MAC address it encountered on which of its links and forwards incoming packets only to their intended recipients. Like a hub, a switch also operates only on the link layer. To the devices in the network, it still seems as if they are directly connected to each other.

- A router inspects and forwards packets on the network layer based on its forwarding table. It can thereby connect several independent networks. Your Wi-Fi router, for example, routes packets within your local network but also between your local network and the network of your Internet service provider. As we will cover in the next subsection, it also provides important services, such as DHCP and NAT.

Maximum transmission unit (MTU)

Link layer protocols usually limit the size of the packets they can forward over the link. This limit is known as the maximum transmission unit (MTU) of the link. For example, the MTU of Ethernet is 1500 bytes. If a packet is larger than the MTU, it is split into smaller fragments by the network layer. If the network drops any of the fragments, then the entire packet is lost.

IP over Avian Carriers (IPoAC)

Written as an April Fools’ joke, RFC 1149 describes a method for delivering packets on the link layer using homing pigeons. While this method is of no practical importance, it shows the flexibility of the Internet layers and is well worth a read.

Network layer

The purpose of the network layer is to route packets between endpoints. It is the layer that ensures interoperability between separate networks on the Internet. As a consequence, there is only one protocol which matters on this layer: the Internet Protocol (IP). If you want to use the Internet, you have to use this protocol. As we’ve seen earlier, packet switching provides only unreliable communication. It is left to the transport layer to compensate for this.

The first major version of the Internet Protocol is version 4 (IPv4), which has been in use since 1982 and is still the dominant protocol on the Internet. It uses 32-bit numbers to address endpoints and routers, which are written as four numbers between 0 and 255 separated by a dot. These IP addresses reflect the hierarchical structure of the Internet, which is important for efficient routing. They are assigned by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), which belongs to the American Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), and by five Regional Internet Registries (RIR). If you’re interested, you can check out the current IPv4 address allocation. There are just under 4.3 billion IPv4 addresses, which are quite unevenly distributed among countries. Given the limited address space, we’re running out of IPv4 addresses. In order to deal with the IPv4 address exhaustion, the Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) has been developed. IPv6 uses 128-bit addresses, which are represented as eight groups of four hexadecimal digits with the groups separated by colons. As IPv6 isn’t interoperable with IPv4, the transition has been slow but steady.

IP geolocation

Since the Internet is not just a protocol but also a physical network, which requires big investments in infrastructure like fiber optic cables, Internet service providers operate regionally. In order to facilitate the routing of packets, they get assigned an IP address range for their regional network. This allows companies to build databases that map IP addresses to their geographical location. Unless you use a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or an overlay network for anonymous communication, such as Tor, you reveal your approximate location to every server you communicate with. Websites such as streaming platforms use this information to restrict the content available to you depending on the country you are visiting the site from due to their copyright licensing agreements with film producers.

One company with such a geolocation database is ipinfo.io. Using their free API, I can tell you where you likely are. If you are visiting this website via a mobile phone network, then the result will be less accurate. If I were to use their paid API, I could also tell you whether you are likely using a VPN or Tor. If you don’t mind revealing to ipinfo.io that you are reading this blog, then go ahead and enter an IPv4 address of interest in the following field. If you leave the field empty, the IP address from which you are visiting this website is used.

Network performance

The performance of a network is assessed based on the following measures:

- Bandwidth indicates how much data can be transferred in one direction in a given amount of time. Unlike memory, which is measured in bytes, bandwidth is usually measured in bits per second, which is written as bit/s or bps. As always, multiples of the unit can be denoted with the appropriate prefix, such as M for mega (106) in Mbit/s or Mbps.

- Latency indicates how long it takes for a single bit to reach the recipient. Latency is usually determined by sending a tiny message to the recipient and measuring the time until a tiny response is received. The result is called the round-trip time (RTT) to that particular destination, which includes the one-way delay (OWD) in both directions and the time it took the recipient to process the request. Have a look at the next two boxes for more information on this.

- Jitter is the undesired variation in the latency of a signal. On the link layer, such a deviation from the periodic clock signal is caused by the properties of the physical medium. The term is sometimes also used to refer to variation in packet delay.

- The bit error rate indicates the percentage of bits that are flipped during the data transfer. As mentioned earlier, data corruption has to be detected and corrected by network protocols.

The term throughput is sometimes used interchangeably with bandwidth. Other times, it is used to refer to the actual rate at which useful data is being transferred. The effective throughput is lower than the maximum bandwidth due to the overhead of protocol headers, packet loss and retransmission, congestion in the network, as well as the delay for acknowledgements by the recipient. More bandwidth doesn’t reduce the latency of Internet communication, which is the crucial factor for applications such as algorithmic trading and online gaming, where latency is called lag. The design of a protocol impacts its performance: The more messages that need to be exchanged in a session, the less throughput you get over long distances due to the many round trips.

You can measure the speed of your Internet connection with tools such as speedtest.net. A high download speed is important for watching high-definition videos and downloading large files, such as computer games and software updates. A high upload speed is important for participating in video calls and uploading large files, such as videos or hundreds of pictures. As a rule of thumb, you can divide the number of megabits per second by ten to get a rough estimate for actual megabytes per second due to the aforementioned overhead. Please keep in mind that Internet communication is routed over many links and that any of the links, including the Wi-Fi link to your own router, can limit the overall performance. For example, if a server you interact with has a slow connection or is very busy, then paying more for a faster Internet at your end won’t improve the situation.

Propagation delay

The physical limit for how fast a signal can travel is the speed of light in vacuum, which is roughly 300’000 km/s or 3 × 108 m/s. It takes light 67 ms to travel halfway around the Earth and 119 ms to travel from geostationary orbit to Earth. While this doesn’t sound like a lot, propagation delay is a real problem for applications where latency matters, especially because a signal often has to travel back and forth to be useful. One party typically reacts to information received from another party, hence it takes a full round trip for the reaction to reach the first party again. The speed at which electromagnetic waves travel through a medium is slower than the speed of light in vacuum. The speed of a light pulse through an optical fiber is ⅔ of the speed of light in vacuum, i.e. 2.0 × 108 m/s. A change of electrical voltage travels slightly faster through a copper wire at 2.3 × 108 m/s. When costs allow it, optical fibers are often preferred over copper wire because they provide higher bandwidth over longer distances with less interference before the signal needs to be amplified. It is to be seen whether satellite constellations in low Earth orbit, such as Starlink, which is currently being built by SpaceX, will be able to provide lower latency transcontinental connections by using laser communication in space. If they succeed, the financial industry will happily pay whatever it costs to use it.

Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP)

The Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) is used by routers to send error messages to the sender of a packet, for example when a host could not be reached or when a packet exceeds its time to live (TTL). ICMP messages are attached to an IP header, in which the IP protocol number is set to 1 according to RFC 792. ICMP complements the Internet Protocol on the network layer. It has various message types, with two of them being commonly used to determine the round-trip time to a network destination. The network utility to do so is called ping. It sends several echo requests and waits for the echo replies before reporting statistics on packet loss and round-trip times:

The first line consists of the command and options that I entered, all the subsequent lines are output by the ping utility.

Round-trip times within the same geographical area are typically below 10 ms, whereas it takes around 80 to 100 ms

to the US East Coast and around 150 to 170 ms to the US West Coast and back from my place in central Europe.

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)

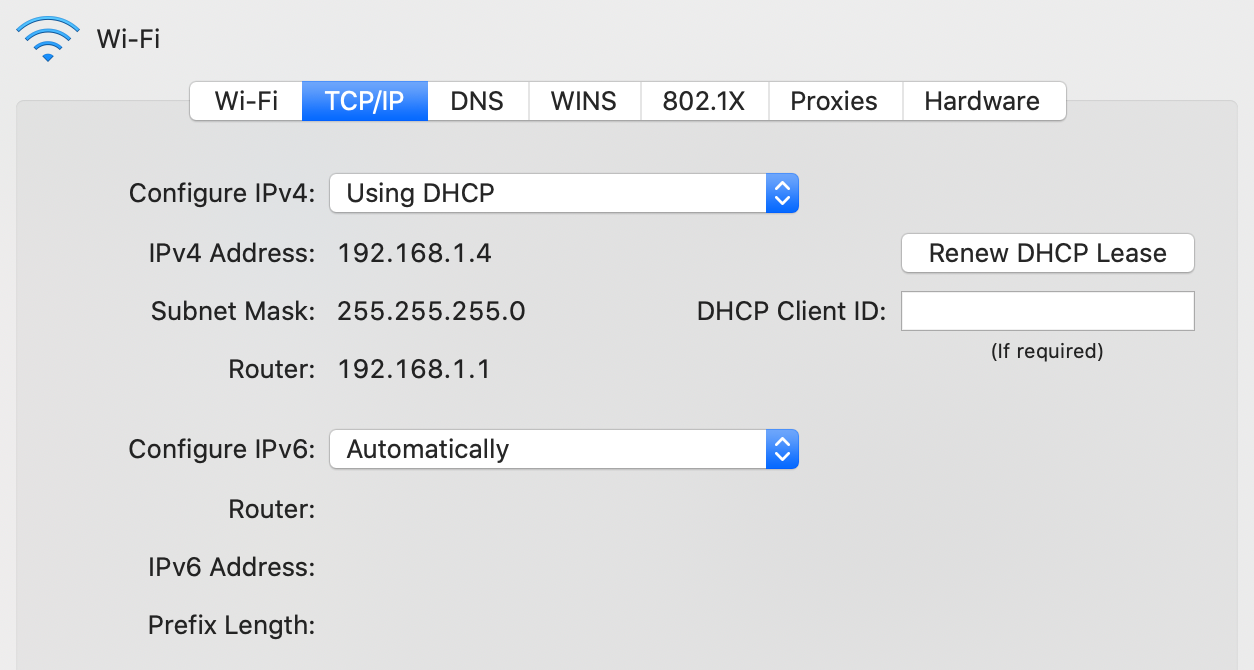

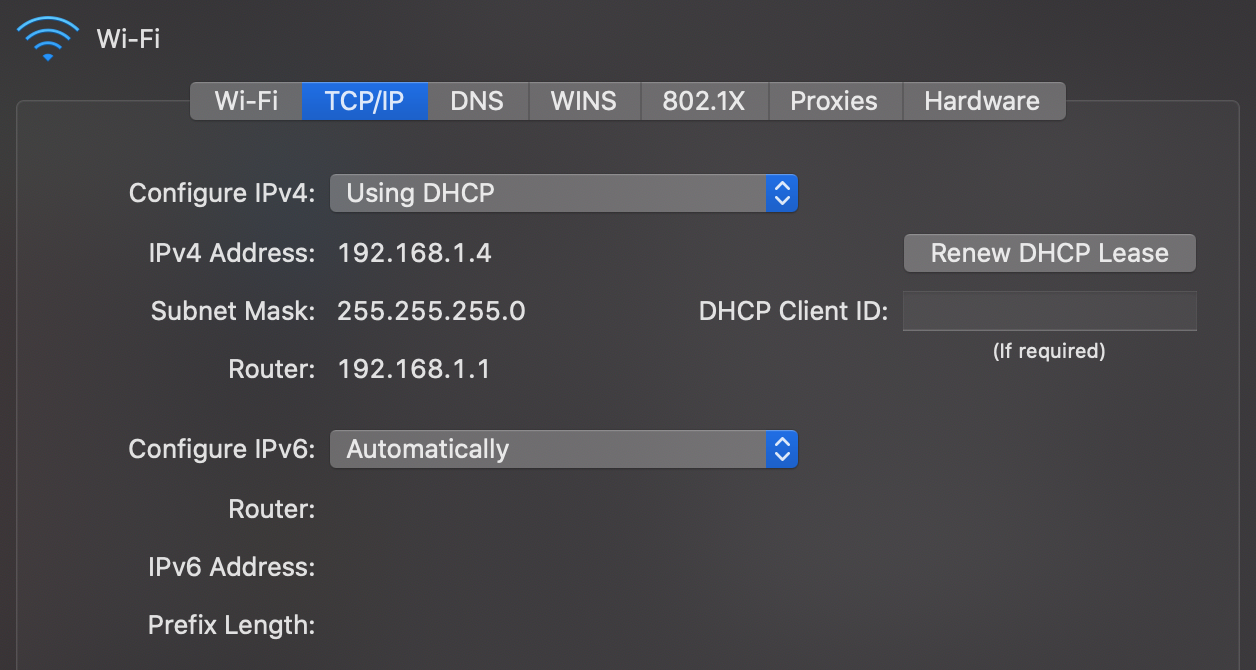

Unlike the MAC address, which at least historically always stayed the same, the IP address of your device is different for every network it joins as IP addresses are allocated top-down to allow for efficient routing between networks. Instead of configuring the IP address manually every time you join another network, your device can request an IP address from the router of the network using the Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). DHCP is an application layer protocol.

Address Resolution Protocol (ARP)

When devices want to communicate with each other in the same network, they need to know the MAC address of the other devices in order to address them on the link layer. The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) resolves IP addresses to MAC addresses in the local network. By using a special MAC address which is accepted by all devices on the local network, any network participant can ask, for example, “Who has the IP address 192.168.1.2?”. The device which has this IP address responds, thereby sharing its MAC address.

Transport layer

Operating systems

Before we can discuss the transport layer, we first need to talk about operating systems (OS). The job of an operating system is to manage the hardware of a computer. Its hardware includes processors, such as the central processing unit (CPU) and the graphics processing unit (GPU), memory, such as volatile memory and non-volatile memory like your solid-state drive (SSD), input/output (I/O) devices, such as a keyboard and a mouse for input, a monitor and speakers for output, as well as a network interface controller (NIC) to communicate with other devices on the same network.

An operating system fulfills three different purposes:

- Abstraction: It simplifies and standardizes the access to the hardware, making it easier for engineers to develop software for several computing platforms.

- Duplication: It provides the same resources to several programs running on the same computer, thereby giving each program the illusion that it has the hardware just for itself.

- Protection: It enforces restrictions on the behavior of programs. For example, it can deny access to the webcam or certain parts of the file system unless the user has granted the necessary permissions.

Port numbers

When a program is being executed, it is called a process. This distinction is important because the same program can be executed several times in parallel, which results in several processes until they terminate. Since more than one process might want to use the network connection at the same time, the operating system needs a way to keep the traffic of different processes apart. The label used for this purpose is a 16-bit integer known as port number. When a process sends a request to another device, the operating system chooses an arbitrary but still unused port number and encodes it as the source port in the transport layer wrapping of the outgoing packet. The recipient then has to include the same port number as the destination port in its response. When the operating system of the requester receives this response, it knows which process to forward the incoming packet to because it kept track of which port numbers it used for which process.

But how does the operating system of the recipient know what to do with the incoming packet? The answer is registration and convention. A process can ask the operating system to receive all incoming packets which have a certain destination port. If no other process has claimed this port before, the operating system grants this port to the process. A port can be bound to at most one process. If it is already taken, then the operating system returns an error. Ports are distributed on a first-come, first-served basis. To claim port numbers below 1024, processes need a special privilege, though. Which port to claim as a receiving process is handled by convention. Each application layer protocol defines one or several default ports to receive traffic on. Wikipedia has an extensive list of established port numbers.

Client-server model

A server is just a process

registered with the operating system to handle incoming traffic on a certain port.

It does this to provide a certain service,

which is then requested by so-called clients.

This is called the client-server model,

which contrasts with a peer-to-peer architecture,

where each node equally provides and consumes the service.

The communication is always initiated by the client.

If the server makes a request itself,

it becomes the client in that interaction.

A server is typically accessed via a network like the Internet

but it can also run on the same machine as its client.

In such a case, the client accesses the server via a so-called loopback,

which is a virtual network interface where the destination is the same as the source.

The current computer is often referred to as localhost.

There is also a dedicated IP address for this purpose:

127.0.0.1 in the case of IPv4 and ::1 in the case of IPv6.

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

The problem with packet-switched networks, such as the Internet, is that packets can get lost or arrive out of order with an arbitrary delay. However, it is desirable for many applications that what the receiver receives is exactly what the sender sent. So how can we get reliable, in-order transfer of data over an unreliable network? This is achieved by the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), which brings the concept of a connection from circuit-switched networks to packet-switched networks. But unlike connections in circuit-switched networks, TCP connections are handled by the communication endpoints without the involvement of the routers in between. In order to provide reliable data transfer, both the sending and the receiving process temporarily store outgoing and incoming packets in buffers. In each direction of communication, the packets are enumerated with the so-called sequence number. For each packet that is being transferred, its sequence number is encoded in the TCP header. This allows the recipient to reorder incoming packets which arrived out of order. By including the sequence number until which they have successfully received all packets from the other party in the TCP header as well, each party lets the other party know that it can remove those packets from its buffer. Packets whose receipts are not acknowledged in this way are retransmitted by the sending party. TCP headers also include a checksum to detect transmission errors. On top of that, TCP allows each party to specify how many packets beyond the last acknowledged sequence number they are willing to receive. This is known as flow control, and it ensures that the sender does not overwhelm the receiver. Last but not least, the sender slows down its sending rate when too many packets are lost because the network might be overloaded. This feature is called congestion control.

IP address spoofing

In all the protocols we have discussed so far, nothing ensures the authenticity of the transmitted information. For example, an attacker can fake their identity by encoding a different source address into the header of a packet. By posing as someone else, the attacker might gain access to a system that they didn’t have before. This is known as a spoofing attack. On the link layer, it’s called MAC address spoofing, and on the network layer, it’s called IP address spoofing.

Since a router connects different networks, it can block packets that come from one network but have a source address from a different network. For packets coming from the outside but claim to be from the local network, this is referred to as ingress filtering. Ingress filtering protects internal machines from external attackers. For outgoing packets that do not have a source address from the local network, the term is egress filtering. Egress filtering protects external machines from internal attackers. As such, the administrator of the local network has fewer incentives to implement this.

The reason why we’re discussing this under the transport layer and not earlier is that TCP makes the spoofing of IP addresses much more difficult. The problem with encoding a wrong source address is that the recipient will send its response to that wrong address. This means that unless an attacker also compromised a router close to the recipient, they won’t receive any of the response packets. Therefore, the interaction needs to be completely predictable for the attack to succeed. Before any actual data can be sent, TCP first establishes a connection by exchanging a few TCP packets without a payload. As we encountered earlier, such preliminary communication in preparation for the actual communication is called a handshake. In a TCP handshake, both parties choose the initial sequence number for their outgoing packets at random. Since the sequence number is a 32-bit integer, which results in more than four billion possibilities, an attacker who doesn’t see the responses from the victim is very unlikely to guess the correct sequence number. Thus, none of the victim’s response packets will be properly acknowledged, which leads to a failed connection on the transport layer before the program on the application layer gets a chance to perform what the attacker wanted.

User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

There is a second important protocol on the transport layer, which I quickly want to mention for the sake of completeness: the User Datagram Protocol (UDP). UDP provides connectionless and thus unreliable communication between processes, encoding only the source and destination port numbers together with a length field and a checksum in its header. It provides none of the other features of TCP, thereby prioritizing fast delivery over reliability. This is useful for streaming real-time data, such as a phone or video call, over the Internet. While the quality of the call deteriorates if too many packets are lost or delayed, there’s no point in insisting on having them delivered as they cannot be played back later. As there is no connection setup and thus no need for a handshake, UDP can also be used to broadcast information to all devices in the same local network.

Network address translation (NAT)

In an effort to conserve IPv4 addresses in order to alleviate the above-mentioned address space exhaustion, all devices in a local network commonly share the same source address when communicating with other devices over the Internet. This is accomplished by requiring that all communication is initiated by devices in the local network and by having the router engage in a technique known as network address translation (NAT). The basic idea is that the router maintains a mapping from the internally used IP address and port number to a port number it uses externally.

| Internal address | Internal port | External port |

|---|---|---|

| 192.168.1.2 | 58’237 | 49’391 |

| 192.168.1.2 | 51’925 | 62’479 |

| 192.168.1.4 | 54’296 | 53’154 |

| … | … | … |

For each outgoing packet, the router checks whether it already has a mapping for the given IP address and source port. If not, it creates a new mapping to a port number it has not yet used in its external communication. The router then rewrites the headers of the outgoing packet by replacing the internal IP address with its own on the network layer and the internal port with the mapped external port on the transport layer. For each incoming packet, the router looks up the internal address and port in its translation table. If found, it replaces the destination address and port of the packet and forwards it to the corresponding device in the local network. If no such entry exists, it simply drops the incoming packet. What makes the technique a bit complicated in practice, is that the router also has to replace the checksums on the transport layer and handle potential fragmentation on the network layer.

From a security perspective, network address translation has the desirable side effect that the router now also acts as a firewall, blocking all unsolicited incoming traffic. This breaks symmetric end-to-end connectivity, though. One of the core principles of the Internet is that any device can communicate with any other device. Given the widespread adoption of NAT, this principle no longer holds nowadays, unfortunately. If you still want to host a server on such a network, you need to configure your router to forward all incoming traffic on a certain port to that machine. This is known as port forwarding. The loss of end-to-end connectivity is also a problem for peer-to-peer applications, which need to circumvent NAT by punching a hole through its firewall or rely on an intermediary server to relay all communication.

Two remarks on the values used in the example translation table above:

- IP addresses starting with 192.168 are reserved for private networks. This address range is often used for local networks behind routers which perform NAT. As a consequence, your network settings might look quite similar to mine.

- Clients can use any port number they like as their source port. If this wasn’t the case, network address translation wouldn’t work. I’ve chosen the values above from the range that IANA suggests for such ephemeral ports.

Server on your personal computer

I said above that a server is just a process registered with the operating system to handle incoming traffic on a certain port. In particular, no special hardware is required; you can easily run a server on your personal computer. In practice, servers run on hardware optimized for their respective task, of course. For example, since the computers in data centers are administrated remotely most of the time, they don’t need to have a keyboard, mouse, or monitor. But there are also other reasons besides hardware why running a server on your personal computer is not ideal:

- Uptime: A server should be online all the time so that others can reach it at any time. If you host, for example, your personal website on your personal computer, you should no longer switch off your computer. Even restarting your computer after installing some updates makes your website unavailable for a short amount of time.

- Utilization: Unless your website is popular, your computer will be idle most of the time. In a data center, several customers can share the same machine, which makes better use of the hardware as well as electricity.

- Workload: If your website does become popular, your personal computer might no longer be powerful enough to serve it. Professional hosting providers, on the other hand, have experience in balancing increased load across several machines.

- Administration: Keeping a service secure and available requires a lot of time and expertise. While this can be a fun and at times frustrating side project, better leave the monitoring and maintenance of your services to experts.

- Dynamic addresses: Once you set up port forwarding on your router in order to circumvent network address translation, you still face the problem that your computer gets a dynamic IP address from the router and that the router typically gets a dynamic IP address from your Internet service provider (see DHCP). In the local network, you can configure your router to always assign the same IP address to your computer based on its MAC address. As far as your public IP address is concerned, your ISP might offer a static address at a premium. Otherwise, you’d have to use Dynamic DNS.

In conclusion, running a production server on your ordinary computer is possible but not recommended. However, software engineers often run a development server locally on their machine, which they then access via the above-mentioned loopback address from the same machine. This allows them to test changes locally before they deploy a new version of their software in the cloud.

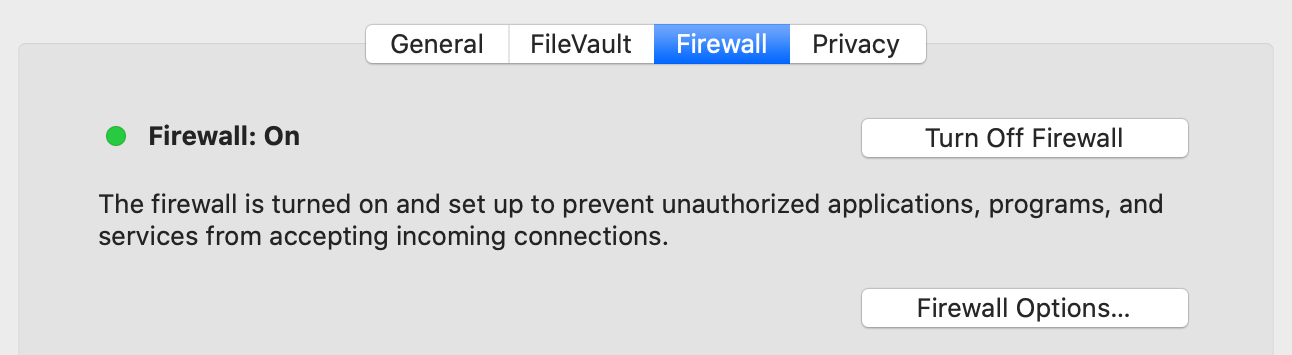

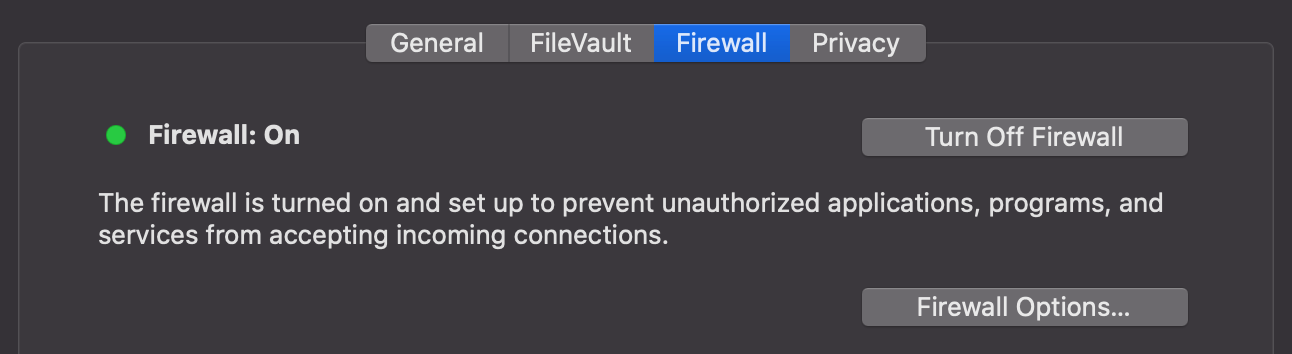

Firewall

A firewall permits or denies network traffic based on configured rules. The goal is to protect the local network or machine from outside threats. In order to compromise your system, an attacker needs to find a hole in the firewall and a vulnerability in a particular application. Having multiple layers of security controls is known as defense in depth. Depending on the firewall and the configured rules, packets are inspected and filtered on the network, transport, or application layer. If the firewall rules are imposed by someone else, such as a network administrator or the government, users might resort to tunneling their traffic via an approved protocol.

Security layer

All the communication we have seen so far is neither authenticated nor encrypted. This means that any router can read and alter the messages that pass through it. Since the network determines the route of the packets rather than you as a sender, you have no control over which companies and nations are involved in delivering them. The lack of confidentiality is especially problematic when using the Wi-Fi in a public space, such as a restaurant or an airport, because your device simply connects to the wireless access point of a given network with the best signal. Since your device has no way to authenticate the network, anyone can impersonate the network and then inspect and modify your traffic by setting up a fake access point. This is known as an evil twin attack, which also affects mobile phone networks. As a general principle, you should never trust the network layer.

Transport Layer Security (TLS)

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is the main protocol to provide confidential and authenticated communication over the Internet. Its predecessor, Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), was developed at Netscape and released in 1995 as version 2.0. In order to increase acceptance and adoption, SSL was renamed to TLS in 1999 after SSL 3.0. TLS exists in the versions 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3. SSL 2.0 and 3.0 as well as TLS 1.0 and 1.1 have been deprecated over time due to security weaknesses and should no longer be used. While it is beyond the scope of this article to explain how the cryptography used in TLS works, this is what it provides:

- Party authentication: The identity of the communicating parties can be authenticated using public-key cryptography. While TLS supports the authentication of both the client and the server, usually only the identity of the server is verified. To this end, the server sends a signed public-key certificate to the client during the TLS handshake. The client then verifies whether the signature was issued by an organization it trusts (see the following two boxes for more information on this). This allows the client to be fairly confident that it connected to the right server without the communication being intercepted by a man in the middle (MITM). While the client could also present a public-key certificate, the client is more commonly authenticated on the application layer, for example with a username and a password.

- Content confidentiality: The content of the conversation is

encrypted in transit with

symmetric-key cryptography.

The shared key

is generated

by the client and the server during the TLS handshake at the start of the session.

Please note that while the content is encrypted,

a lot of metadata is revealed

to anyone who observes the communication between the two parties.

An eavesdropper learns that

- a TLS connection was established between the two IP addresses,

- the time and duration of the connection, which leaks a lot, given that a response often triggers follow-up connections,

- the rough amount of data that was transferred in each direction,

- and the name of the server because the server sends its certificate in plaintext to the client. Additionally, the client likely did an unencrypted DNS query beforehand; the attacker can perform a reverse DNS lookup of the server’s IP address; and the client might indicate the desired host name to the server so that the server knows which certificate to send back.

- Message authentication: Each transmitted message is authenticated with a so-called message authentication code. This allows each party to verify that all messages were sent by the other party and that the messages were not modified in transit. Encryption alone usually does not guarantee the integrity of the encrypted data because encryption generally does not protect against malleability. What TLS does not provide, however, is non-repudiation. Or put another way: A party can plausibly dispute that it communicated the statements inside a TLS connection. This is because message authentication codes are symmetric, which means that whoever can verify them can also generate them.

Since TLS requires reliable communication, it uses TCP on the transport layer.

Digital signatures

The essential feature of signatures is that they are easy for the author to produce but hard for others to forge. Since digital information can be duplicated and appended without degradation, a digital signature has to depend on the signed content. Handwritten signatures, on the other hand, are bound to the content simply by being on the same piece of paper.

Digital signature schemes consist of three algorithms:

- Key generation: First, the signer chooses a random private key, from which they can compute the corresponding public key. The signer should keep the private key to themself, while the public key can be shared with anyone. Both keys are usually just numbers or pairs of numbers in a certain range. For the digital signature scheme to be secure, it has to be infeasible to derive the private key from the public key. This requires that one-way functions, which are easy to compute but hard to invert, exist. It is widely believed that this is the case but we have no proof for this yet. An example of such an asymmetric relationship is integer multiplication versus integer factorization. While the former can be computed efficiently, the latter becomes exceedingly hard for large numbers.

- Signing: The signer then computes the signature for a given message using the private key generated in the previous step. The signature is also just a number or a tuple of several numbers. Since the computation of the signature depends on the private key, only the person who knows the private key can produce the signature.

- Verification: Anyone who has the message, the signature, and the signer’s public key can verify that the signature was generated by the person knowing the corresponding private key.

As you can see from these algorithms, digital signatures rely on a different authentication factor than handwritten signatures. While the security of handwritten signatures relies on something the signer does with their fine motor skills, the security of digital signatures relies on something the signer knows or rather has. In theory, a private key is a piece of information and thus knowledge. In practice, however, a private key is usually too big to remember and thus rather a piece of data that the user has. Since the private key is not inherent to the signer but rather chosen by the signer, digital signatures require that the signer assumes responsibility for the signed statements. This brings us to the next topic: public-key infrastructure.

Public-key infrastructure (PKI)

How do you know that someone took responsibility for all signatures which can be verified with a certain public key if you have never met them in person? In the absence of knowledge like this, you cannot authenticate anyone over an insecure channel. However, if you know the public key of some individuals, you can verify whether or not they signed a certain statement. A statement can be of the form: “Person … told me that their public key is …”. If you know the public key of the person who signed such a statement and if you trust this person to sign only truthful statements, then you just learned the public key of another person. With this technique, you can now authenticate someone you have never met before as long as you have met someone before who met that someone before. For example, if you met Alice at some point and received her public key directly from her, you can authenticate Bob over an untrusted network if Alice met Bob and confirms to you (and everyone else) that a specific public key indeed belongs to Bob. Whether Alice sends the signed statement with this content directly to you or whether Bob presents this signed statement during the conversation with him, does not matter. Since you know the public key of Alice, you can verify that only she could produce the signature. In order to make the system scale better, you can decide to also trust Bob’s statements regarding the public key of other people, in particular if Alice decided to trust Bob in this regard. This makes trust transitive: If you trust Alice and Alice trusts Bob, then you also trust Bob.

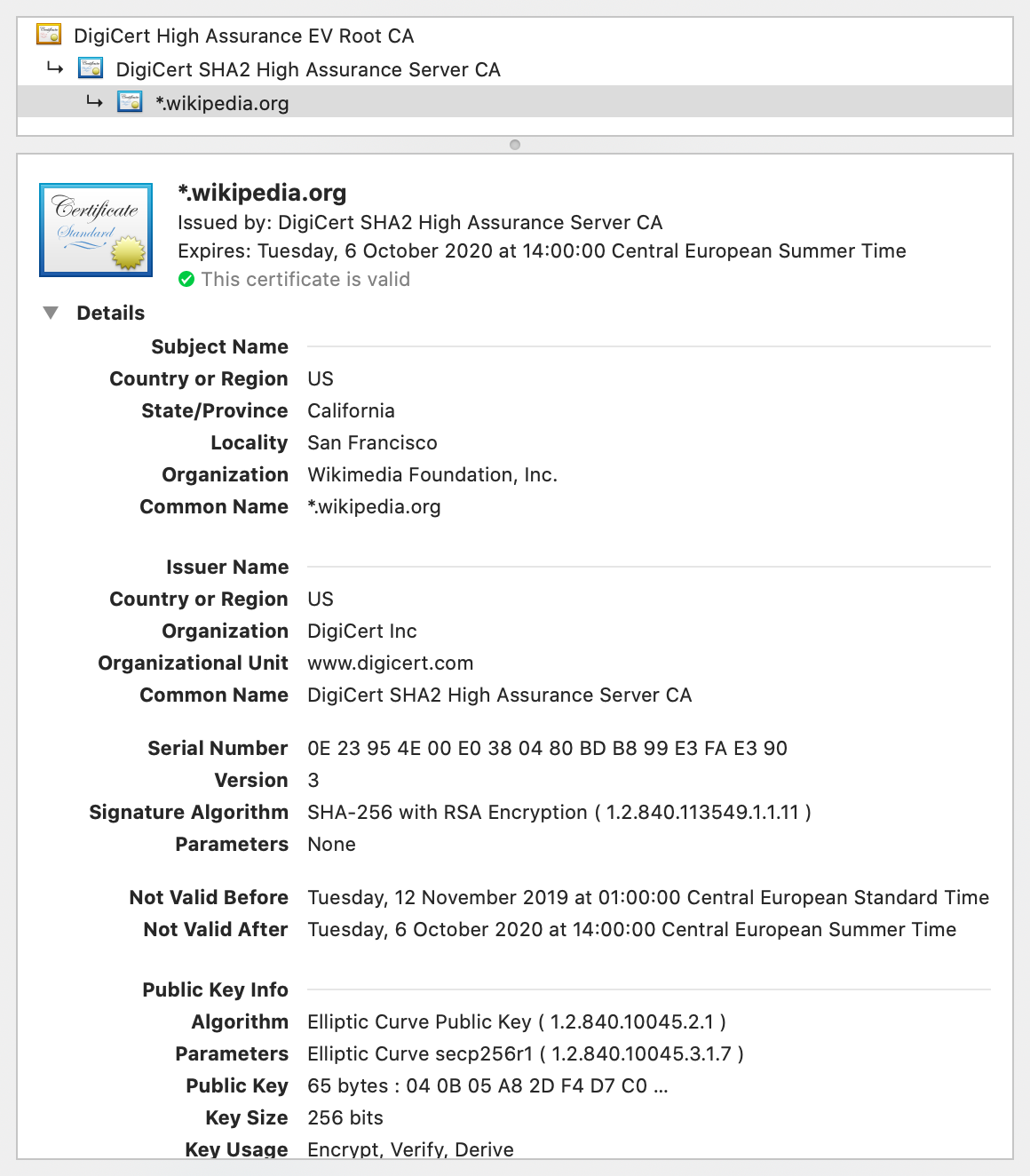

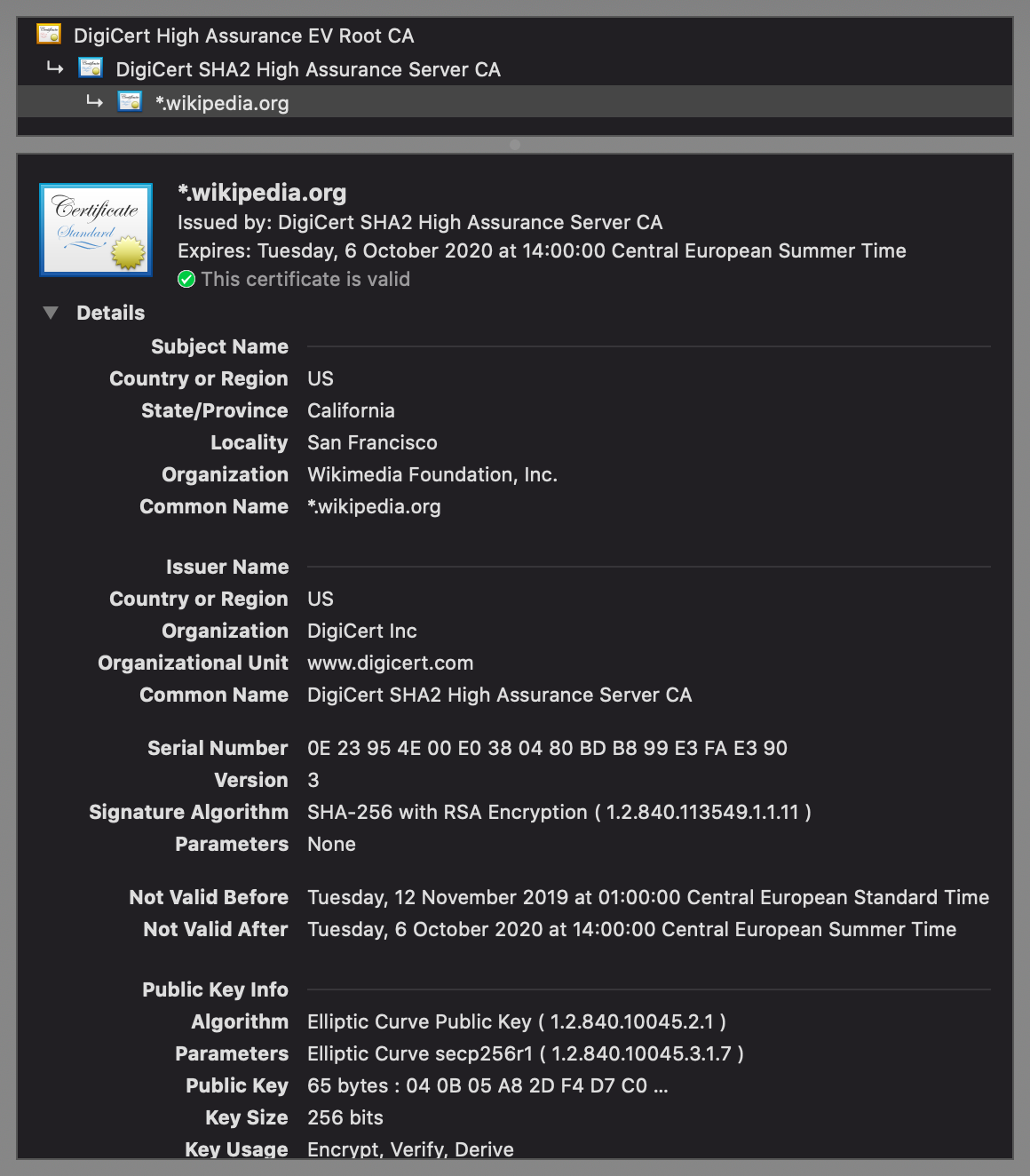

Signed statements of the above form are called public-key certificates. A widely adopted format for public-key certificates is X.509, which is also used in TLS. X.509 certificates are often displayed as follows:

There are two different paradigms for issuing public-key certificates:

- Web of trust: As described above, you start out with no trust and then expand your circle of trust by meeting people and verifying each other’s public key. This is done most efficiently at so-called key-signing parties, where participants verify each other with state-issued identity documents. The big advantage of this paradigm is that it is completely decentralized, requiring no setup and no trusted third party. On the other hand, it demands a lot of diligence from individual users. Additionally, every user has a different view of which identity assertions can be trusted. While this works reasonably well for social applications such as messaging, such a fragmented trust landscape is not ideal for economic interactions.

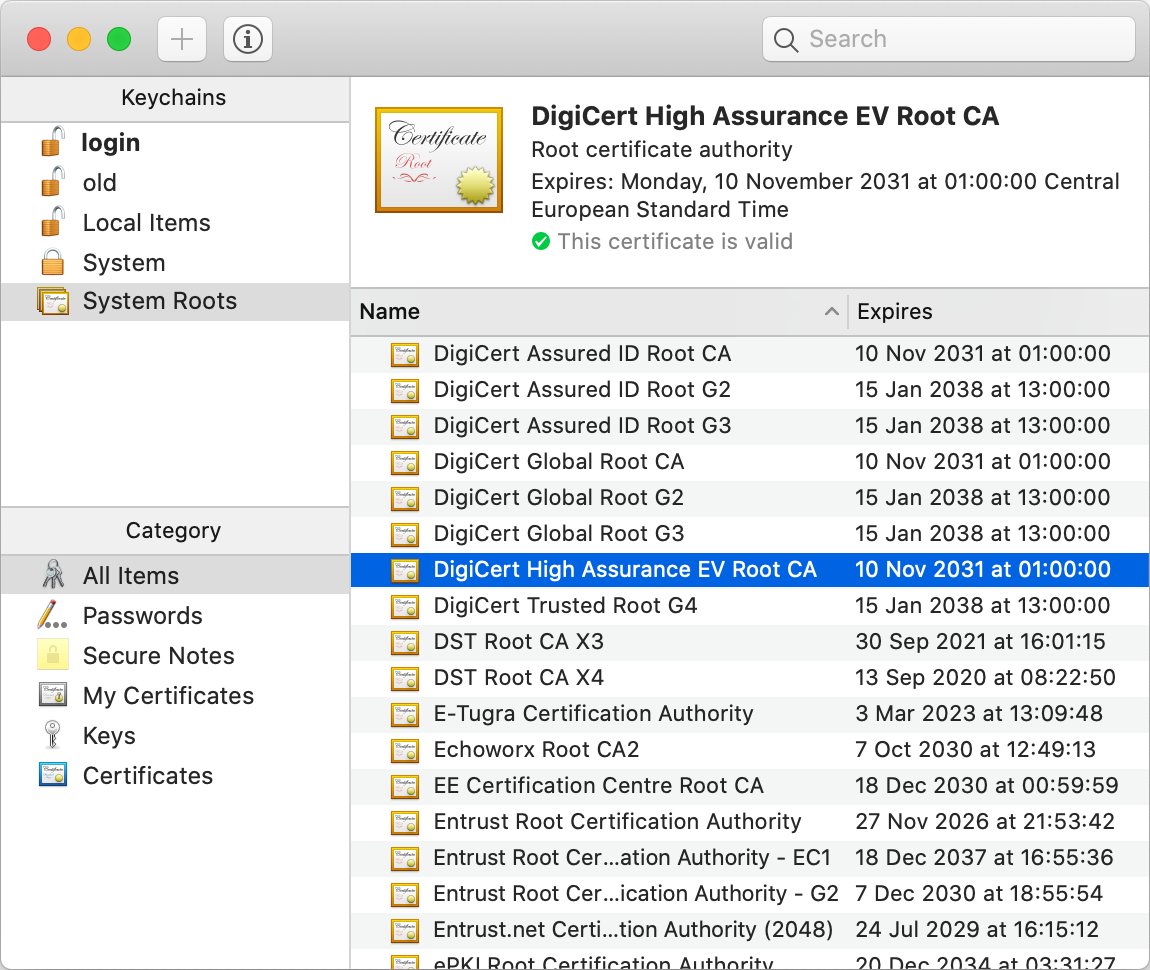

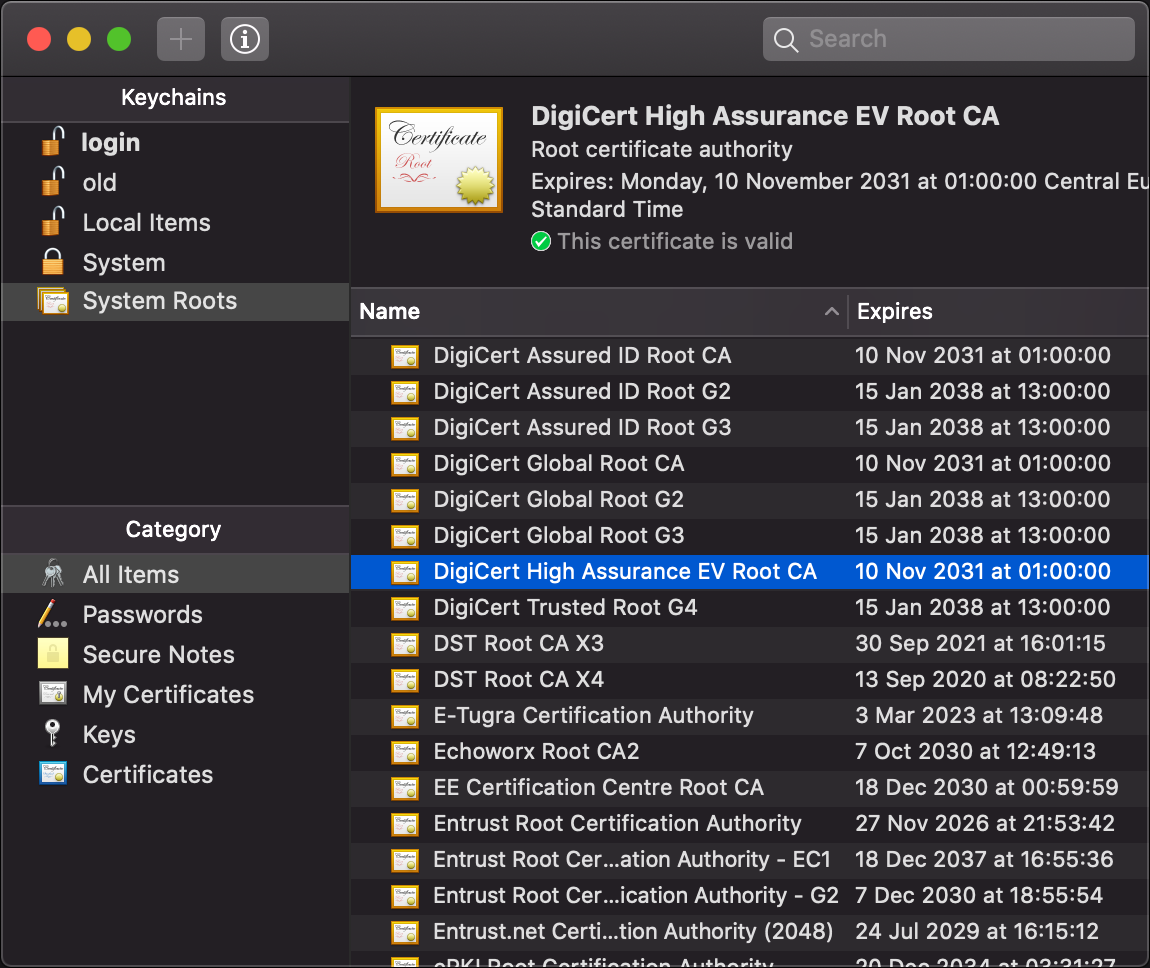

- Certification authorities (CAs): In the other, more common paradigm, manufacturers deliver their devices or operating systems with a preinstalled list of trusted third parties to their customers. An employer might replace or extend this list on corporate devices. These trusted third parties are called certification authorities (CAs). While users can add and remove CAs on their own devices, they rarely do this – and I don’t recommend to mess with this list either, as badly informed changes can compromise the security of your system. Organizations and individuals pay one of these CAs to assert their identity. A preinstalled CA, also known as a root CA, can also delegate the authority to certify to other entities, which are called intermediate CAs. If you have a look at the top of the above screenshot, then you see that this is exactly what happened: The root CA DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA delegated its authority with a signed certificate to the intermediate CA DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA, which in turn signed that the public key at the bottom of the screenshot, of which only the beginning is displayed by default, belongs to the Wikimedia Foundation as the subject of the certificate. If we check the list of root CAs, we see that DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA is indeed among them:

As described above, the server sends its certificate to the client during the TLS handshake. By also including the certificate of a potential intermediate CA, the client has all the information needed to authenticate the server. This means that CAs don’t have to be reachable over the Internet, which is good for the security of their signing keys but also good for the reliability of the Internet. There is a lot more to public-key certificates, such as expiration and revocation, but these aspects are beyond the scope of this article.

Application layer

Everything we’ve covered so far serves a single purpose: to accomplish things we humans are interested in. This is done with protocols on the application layer. Examples of application layer protocols are the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) as the foundation of the World Wide Web (WWW), the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) for delivering email, the Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) for retrieving email, and the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) for, as you can probably guess, transferring files. What all of these protocols have in common is that they all use a text-based format, that they all run over TCP, and that they all have a secure variant running over TLS, namely HTTPS, SMTPS, IMAPS, and FTPS. This is the beauty of modularization: Application layer protocols can reuse the same protocols below, while the protocols below don’t need to know anything about the protocols above.

Text encoding

Similar to numbers, human language is also encoded with symbols. By assigning meaning to specific combinations of symbols, which we call words, we can encode a large vocabulary with relatively few symbols. In computing, the symbols which make up a text are called characters. English texts consist of letters, digits, punctuation marks, and control characters. Control characters are used to structure texts without being printed themselves. So-called whitespace characters, such as space, tab, and newline, fall in this category. Other examples of control characters are backspace, escape, the end-of-transmission character, and the null character to indicate the end of a string. (A string is just a sequence of characters in memory.)

In order to uniquely identify them, a so-called code point is assigned to each character. A code point is just a number, which itself needs to be encoded in order to store or transmit text. In order to understand each other, two or more parties need to agree on a common character encoding. After the Morse code for telegraphs, the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), which was developed in the 1960s, became the first widely adopted character encoding for computers. Based on the English alphabet, ASCII specifies 128 characters and how they are encoded as seven-bit integers. It is basically just a table mapping characters to their code points and vice versa. Since it’s easier to reserve a whole byte for each character, the eighth bit made it possible to extend ASCII with 128 additional characters. Many companies used this for proprietary extensions, before the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published ISO 8859 in 1987, which standardized character sets for Western European languages, Eastern European languages, and others.

The character encodings defined by ISO 8859 have the problem that they are not compatible with each other. Since character encodings are typically used for whole documents including websites and not just parts of them, you cannot use characters from different sets in the same document. Additionally, each document has to be accompanied with the used character set as part of its metadata because none of the encodings will ever be in a position to supersede them all as a widely accepted default encoding. Unicode, which is maintained by the California-based Unicode Consortium, unifies different character sets by providing a unique code point for every imaginable character. Unicode specifies different encodings for these code points, which are known as Unicode Transformation Formats (UTF). The most popular ones are UTF-8, which uses one to four bytes for each code point and maximizes compatibility with ASCII, and UTF-16, which uses one or two 16-bit units per code point.

Text-based protocols

A communication protocol has to specify

how text and numbers in messages are encoded

or at least how the recipient is informed about the used encoding.

As mentioned above,

many application layer protocols are

text-based,

which means that the transmitted messages can be meaningfully displayed in a text editor.

This is in contrast to binary protocols,

whose messages are difficult to read for humans without specialized analysis software.

As we just learned, text is also encoded with binary numbers,

and text editors can be considered as specialized software.

The real difference between the two categories of protocols is

that text-based protocols delimit different pieces of information

with a certain character, such as a newline or a colon, at that position,

whereas binary protocols often define specific lengths in bytes for each

field

or prefix a field with its length in bytes.

The advantage of binary protocols is

that they can directly incorporate arbitrary data,

whereas the data in text-based protocols needs to be

escaped

in order to ensure that the delimiting character does not occur within a field.

If, for example, different header fields are separated by a newline,

then none of the header fields may contain a newline character.

If they do, the newline character needs to be replaced

with the appropriate escape sequence

as defined by the protocol.

A common escape sequence for a newline character is \n.

Alternatively, the whole data could be re-encoded with a certain set of characters.

This is required when arbitrary data needs to be encoded

where only text is permitted or reliably supported.

This is the case for email attachments

because email originally only supported 7-bit ASCII.

If you attach a picture to an email, for example,

then the picture is split into chunks of 6 bits,

and each chunk is encoded with one of 64 characters.

This encoding is called Base64,

and it needs to be reverted by the recipient

in order to display the picture.

Base64 uses the characters A – Z, a – z, 0 – 9, +, and /

(26 + 26 + 10 + 2 = 64).

Since binary protocols require no such transformation

and often skip the labels for fields

or abbreviate them to a single number,

they are more concise and efficient than text-based protocols.

HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

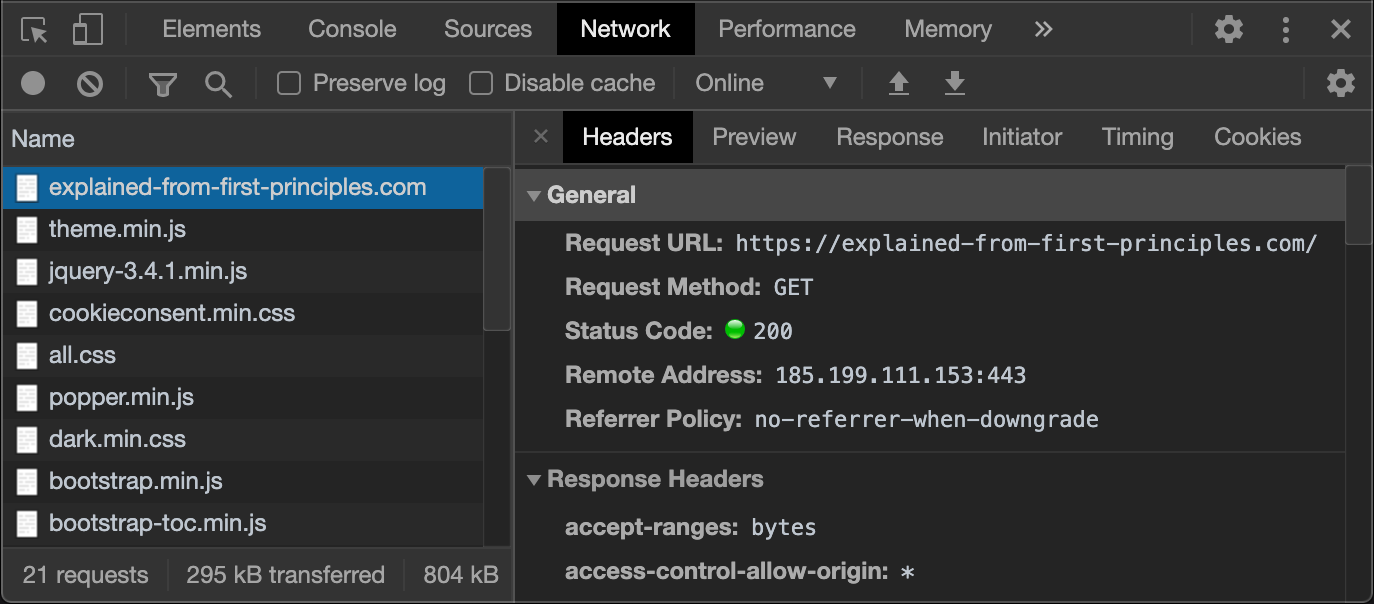

In order for you to read this article,

your browser fetched this page from a

web server via HTTP over TLS,

which is known as HTTPS.

Given the popularity of the Web,

HTTP is one of the most widely used application layer protocols.

If we ignore newer versions of the protocol and rarely used features,

HTTP is a fairly simple protocol and thus an excellent first example.

HTTP works according to the client-server model:

The client sends a request, and the server sends back a response.

The first line of the request starts with the

request method,

which specifies whether the request is about

retrieving (GET) or submitting (POST) data.

The request method is followed by

the resource to retrieve or submit to

and the protocol version.

The first line of the response includes the

status code,

which indicates whether the request was successful

and, if not, what went wrong.

While the first line is different,

both HTTP requests and responses continue with

header fields

(formatted as name: value on separate lines),

an empty line,

and an optional message body.

If you request a file,

the body of the request is usually empty,

whereas the body of the response contains the file

(assuming that the request was successful).

If, on the other hand, you submit data,

such as your username and password in a login form,

the request contains this data in its body,

whereas the body of the response could be empty,

for example, when your browser is being redirected to a different page.

We have encountered the concept of header and payload several times already,

and HTTP follows the same logic.

Let’s look at a slightly modified example from

Wikipedia:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.0

Host: www.example.com

/index.html from the host www.example.com.

Please note that the request is terminated by an empty line and has no message body.

The only mandatory request header field is Host.

It is required to let the server know

from which website to serve the requested resource

in case the same server hosts several websites.

As you learned above,

only one process can bind to a specific port on the same machine,

thus this header field is the only way for a server

to tell the requests to different websites apart.

(Strictly speaking, it’s one process per port number and IP address.

So if the server has several network interfaces,

the requests on each interface could be handled by a different process.)

The default port is 80 for HTTP and 443 for HTTPS.

If you want to request a website on a different port,

you would specify this after the host name in the

URL.

For example, if you run a web server locally on port 4000,

you would access it at http://localhost:4000/ in your browser.

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Date: Mon, 23 May 2005 22:38:34 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 155

Last-Modified: Wed, 08 Jan 2003 23:11:55 GMT

Server: Apache/1.3.3.7 (Unix) (Red-Hat/Linux)

<html>

<head>

<title>An example page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello, World! This is a very simple HTML document.</p>

</body>

</html>

As indicated by the Content-Type header field,

the response is an HTML document.

HTML stands for HyperText Markup Language

and is the document format of the Web.

The browser parses the HTML document

and displays it as a website.

<p> stands for a paragraph, which is then closed by </p>.

The other so-called tags

in the example above should be self-explanatory.

Usually, a website references other files from its HTML,

such as styles,

scripts,

and images.

These files can be hosted on the same or a different server.

The browser fetches them via separate HTTP requests.

The body of the response is not limited to text-based formats,

any files can be transferred via HTTP.

Thanks to the Content-Length header field,

binary files don’t need to be escaped.

Every modern browser includes powerful

developer tools,

with which you can inspect the requests it made:

If you are familiar with the command-line interface